Robert Ragsac: History Detective

- Date

-

June 18, 2024

- Location

-

De Anza College

- Interviewers

-

Mae Lee and Karen Wang

- Interviewee

-

Robert Ragsac (b. 1931)

- Transcript

"Asian American History is Like a Beach"

This is a story of an Ilokano boy, a Second-Wave immigrant, a son of migrant Filipino laborers who settled in San Jose during the Great Depression. But it’s also a story about Escalante's pool hall on Sixth Street, the Dobashis' grocery store on Jackson, and the basketball games between the Filipino kids and Nissei Zebra Bs in the old gym of the Buddhist Church.

It’s a story of a neighborhood, its people, and its memories—and a history detective’s efforts to document them before they are erased by the receding waves of time.

![]()

American history does not include [Filipino Americans] at all...if you're not white, you're not part of American history.

- Robert Ragsac, oral history, 2024

A First Generation Fil-Am Looks Back

In 2005, at a friend's funeral, Robert ran into a Filipino American poet named Al Robles and started talking about their generation—the children of the First-Wave Filipinos who migrated to the United States in the 1920s and 1930s.

"You know," Al said, "there's a lot of us that have not documented our stories. Robert, why don't you write something about that?"

Robert was caught off guard. "What? I never even thought of that."

"Yeah, you know," Al said. "Just write something about what it was like when you were growing up."

"That's a good idea," Robert said.

It took Robert about two or three years to write the retrospective because he was still working full-time. But he finally finished it, and called up Al, eager to share his work.

"Al, let's meet sometime, because I got it done. What do you want to do about it?"

Al said, "Okay, let's meet."

"All right," Robert replied. "I'll give you a call when I got free time."

But when Robert called again, Al had passed away.

And this is the lesson Robert learned: don't wait. If you're going to interview someone, share a story, or put something down on paper, do it now. Because time doesn't wait either, and you never know when it might be too late.

![]()

No more do I hear the young Ilokanos of my childhood...The voices of that First Wave of Ilokano immigrants...are long stilled but clearly remembered.

- Robert Ragsac, "A First Generation Fil-Am Looks Back" retrospective, 2008

The Power of Community and Collective Memory

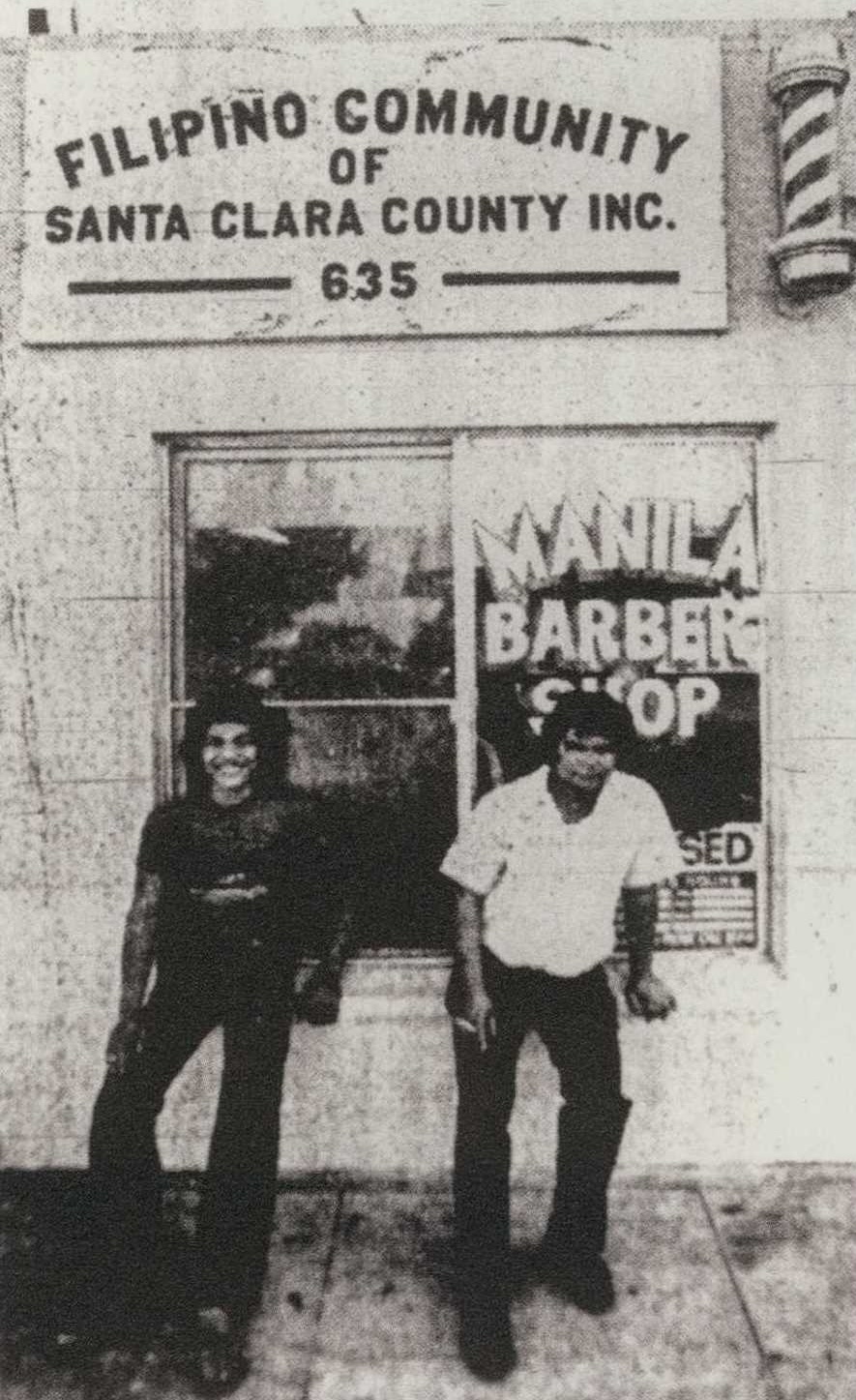

Right: Two Pinoys in front of the Manila Barbershop located in the Filipino Community hall on 6th Street (circa 1970s). Photo courtesy of "San Jose Japantown: A Journey."

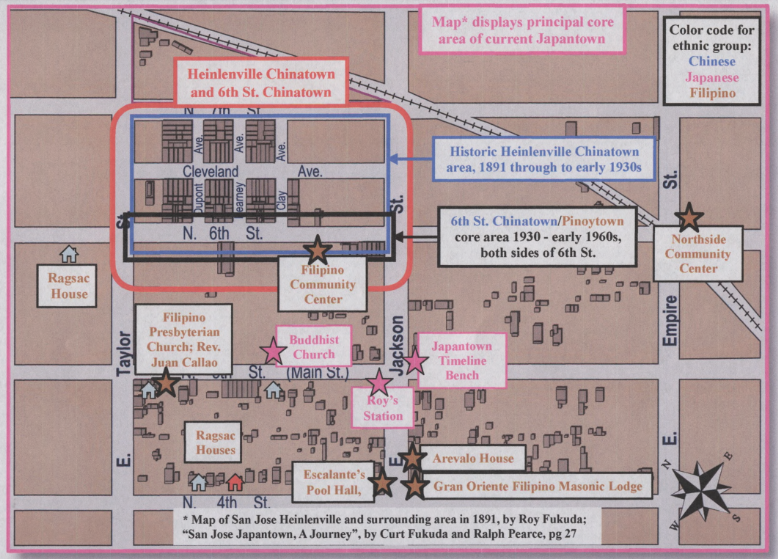

In the 1970s, Robert volunteered with an organization helping older Filipinos and new immigrants adjust to life in America. Though his involvement was short-lived, it laid the foundation for a connection that would resurface decades later. In 2006, Robert met Ralph Pearce and Curt Fukuda, who were working on a book about the history of San Jose’s Japantown. They wanted to expand beyond the stories of the Issei and Nisei to include the experiences of other ethnic groups, such as the Chinese and Filipinos, who had also shaped the community.

Eager to contribute, Robert reached out to members of his generation of Second-Wave immigrants, as well as the remaining First-Wave Filipinos. Unfortunately, by that time, many of them had already passed away. To preserve their remaining stories, Robert and his cohort organized interviews where people brought photo albums, old books, as well as siblings or friends who might help piece together shared memories.

Left: Frances Bacosa, Henrietta Villaruz, and Lily Bacosa stand in front of the Universal Cafe owned by the Bacosa family (circa 1940s). Photo courtesy of "San Jose Japantown: A Journey."

They would gather in someone’s home, sit down with the photographs, and record everything. “If you just interview one person, you [only] have their memories,” Robert said. “I always say my sisters have better memories than I do about what happened around us.” Together, they would pore over the images, asking questions like, “What’s this? Who is that? When and where was this taken?”

These sessions yielded an abundance of material—video recordings, photographs, and stories—that were integral to the Japantown book. When Robert finally saw the published book, it dawned on him the importance of what they were doing. “I didn’t think [our stories] were historically important until the book…came out,” he said. He described feeling like a part of the history of this place. “You look at the index, that’s my name, my sister’s name, my buddies, my friends, the old Pinoys.”

![]()

I didn't think our stories were historically significant until the book came out.

- Robert Ragsac, oral history, 2024

Talking Stories: How the Pinoytown Tours Came About

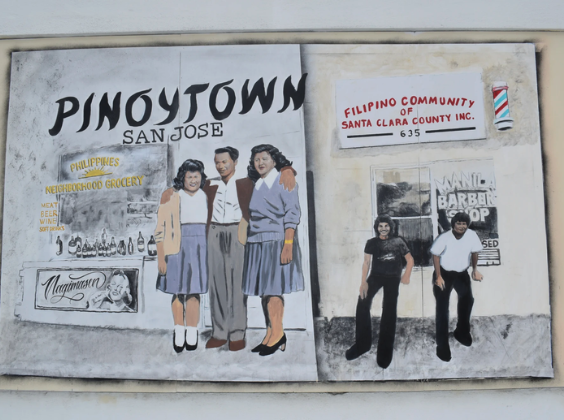

Above: Filipino businesses such as Supnet's Variety Store and the Universal Cafe operated on 6th Street in the heyday of San Jose's Pinoytown in the 1940s and 1950s. Photo courtesy of "San Jose Japantown: A Journey."

One day, Robert was sitting around talking to his buddies and reminiscing about old times.

“Hey, do you remember the Dobashis, and the Buddhist temple? And how about when we played basketball against the Zebra Bs?” someone asked.

Robert said, “Maybe, we ought to walk around, just among us.”

So, the three or four of them took a stroll through the neighborhood, just talking stories.

“Do you remember Toshi’s, with the fountain there?”

“Oh yeah, and Tom and Mary’s?”

As they turned and walked down Sixth Street, someone said, “Oh yeah, remember Escalante’s pool hall?”

“Yeah, and how about the time when all these Filipinos were out there on the street?”

And at some point, Robert thought to himself, “I wonder if somebody else would be interested in this.”

In 2018, he decided to organize an informal tour. No sign-ups, just an open invitation for anyone interested to join. He scheduled it for spring of 2019, and put together a simple pamphlet using PowerPoint with the meeting location at the Japantown bench on Fifth and Jackson. He printed out 10 copies. 25 people showed up.

One of the attendees was Ann Regino, a head of the Santa Clara Valley chapter of the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS). It turns out, she liked the tour so much that she approached Robert with the idea of making it an official FANHS program.

Today, the FANHS Pinoytown Tour is led by trained docents, and shares the story of the Filipino American community in San Jose to individuals, organizations, and students of Asian American and Filipino American Studies.

“So that’s how the Pinoytown tours came about," Robert reflected. "Because of the germ [that] started with Al Robles…and then, of course, with Ralph and Curt, it became even larger than I could ever have imagined.”

Above: The Pinoytown mural, painted by Annalyn Bones and Jordan Gabriel, at the corner of 6th and Jackson in San Jose.

![]()

Because of the germ that started with Al Robles...and then, of course, with Ralph and Curt, it became even larger than I could ever have imagined.

- Robert Ragsac, oral history, 2024

Tides of Migration: A Walk Down History Lane

Right: Robert's father, Sergio "Sharkey" Ragsac, as a sixteen year old in 1923. Photo courtesy of the Ragsac family.

Following the United States' victory in the Spanish-American War, the Philippines was ceded to the U.S. under the Treaty of Paris in 1898. However, after three centuries of Spanish colonial rule, Filipinos sought independence rather than subjugation under another foreign power. This led to the bloody Philippine-American War, which lasted until 1902 when the U.S. ultimately defeated Filipino nationalists. As a result, the United States formally took control of the Philippines.

Under what Dr. Rick Baldoz of Brown University calls a “paternalistic racial ideology,” the U.S. allowed Filipinos to migrate to the mainland—but under heavily restricted, racially classified conditions. As U.S. nationals but not citizens, Filipinos were denied the right to vote, own property, establish businesses, or receive legal protections against race-based labor exploitation.

This system proved profitable for some. Shortly after the U.S. annexation, the Hawaii Sugar Planters’ Association recruited Filipino laborers to work on plantations. Filipino workers were seen as ideal—hardworking, reliable, and willing to toil for low wages. By the 1920s, a steady stream of Filipino migrants were arriving in Hawaii, and some later moved to the mainland.

Left: The Ragsac family circa 1930s

Among them were Robert’s parents, Sergio Reg and Mary Vidal Ragsac. Originally laborers in Hawaii, they migrated to California in 1927, eventually settling in San Jose. It was there, at 648 North 4th Street, that Robert was born in 1931.

After the Philippines gained independence, the Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1934 reclassified all Filipinos as aliens and imposed a strict quota of just 50 immigrants per year. This, Robert said, contributed to the erasure of Filipino American history. “There was no presence—no one interested in documenting Filipinos or Filipino history,” he said. “Or, for that matter, Chinese and Japanese history as part of American history.”

![]()

There was no presence—no one interested in documenting Filipinos or Filipino history.

- Robert Ragsac, oral history, 2024

He added, “It does my heart really good when I see people…supporting what I call the Fil-Am history here in the United States.“

How to Become a History Detective

“When I talk to the students and I give this story, it’s a revelation to them that there is…a history of the Filipinos before them. And the reaction I get sometimes is that, ‘Gee, maybe we’re becoming part of it. I say, 'Yes, you are, you should be. Becoming part of American history.'”

“Every time I end a talk, I say, ‘You know, I was a student once too. And I’d sit there and listen to this lecture in history. And I said, ‘Well, that’s really great. Go out the door. 90 percent of it will vanish, right?’”

“But here are two things that I want you to remember. One, you write your mom and dad’s story. Second, write a family tree.”

“Why do I do that? Because someday, somebody, a historian, is going to say, ‘Wasn’t your family involved with that nurse’s riot, and it was led by a Filipino. Wasn’t your mom a nurse?’ And unless you had that story, you might think, ‘What? Yeah, I know my mom was a nurse, but I don’t know what she did or what she was part of.’”

“The First Wave is the Filipino immigrants that came in the 1920s and 30s…I’m the Second Wave. My son is a Third Wave. But the waves are receding.”

So here’s Robert’s lesson for you: write down your family's story! One day, it might become a part of history.

Above: Map of San Jose Japantown overlaid with historical and present-day Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino landmarks. Courtesy of Robert Ragsac, 2024.

Here are two things that I want you to remember. One, you write your mom and dad's story. Second, write a family tree.

- Robert Ragsac, oral history, 2024

Where Next?

Learn More

- "San Jose Japantown: A Journey," Curt Fukuda and Ralph M. Pearce, originally published 2014 - a book chronicling the history of San Jose's Japantown, from its 19th-century origins adjacent to Heinlenville Chinatown to the present-day.

- "A First Generation Fil-Am Looks Back," Robert Ragsac, published October 14, 2008 - a retrospective on the Ragsac family and San Jose's Pinoytown from the 1930s to 1960s.