Connie Young Yu: Writing Untold Stories

- Date

-

June 11, 2024

- Location

-

De Anza College

- Interviewers

-

Mae Lee and Karen Wang

- Interviewee

-

Connie Young Yu (b. 1941)

- Transcript

Connie's Journey

Connie grew up with her family’s stories, and she was proud of her Chinese American identity. Her great-grandfather had worked on the Transcontinental Railroad, and her father was born in Heinlenville—one of San Jose’s historic Chinatowns. Yet through these stories, she also learned about the racism and discrimination her family endured.

However, it wasn’t until college when a professor’s patronizing remark unintentionally prompted her to begin connecting her family’s struggles and experiences to broader American history. This would set her on a lifelong journey to become a writer of “untold stories.” Years later, she would return to her father's birthplace to write its legacy—as the first Asian American community in the Santa Clara Valley—back into history.

With Asian American Studies, it's the people's history. It's all oral history. It didn't come out of libraries, you know

- Connie Young Yu, oral history, 2024

Discovering Her Calling: Mark Twain and the Chinese

Connie attended Mills College, where she excelled in poetry and wanted to become a creative writer. At the time, her school was predominantly white. During her senior seminar, in which she was the only person of color, the professor assigned her to write about Mark Twain and the Chinese.

Despite feeling singled out because of her race, Connie said in hindsight that her professor unintentionally did her “the biggest favor of my life.” Through researching her senior thesis, she found that Mark Twain was an advocate for the Chinese who spoke out against the violence they faced during the late 19th century, an era of widespread anti-Chinese sentiment and exclusion.

It suddenly connected me to the history that I always felt and knew about.

- Connie Young Yu, oral history, 2024

For Connie, this echoed the experiences of her paternal grandfather, who immigrated to San Jose as a young boy, just one year before the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was passed. One day, he was coming home from work when he encountered a group of white kids who started chasing him. He ran as fast as he could back to the safety of Chinatown, and lost his hat in the process. Connie recalled how matter-of-fact her grandfather was about this disturbing experience. “It seemed like it was part of being in America,” she said.

Making Her Mark: The Unsung Heroes of the Golden Spike

In 1969, Philip Choy, then president of the Chinese Historical Society of America, was invited to speak at the 100th Anniversary of the Golden Spike commemorating the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad.

In anticipation of the event, Connie researched and wrote an article titled “The Unsung Heroes of the Golden Spike,” which was published in the San Francisco Examiner. Connie's research revealed the systemic erasure of the Chinese railroad workers, such as her maternal great-grandfather, whose remarkable achievements and sacrifices had been written out of history.

Philip's speech was a long-awaited chance to restore dignity and humanity to the thousands of workers whose stories had been ignored. However, just before he was scheduled to speak, the event’s chairperson told him, “Oh, I’m sorry Mr. Choy, there’s no time for you”—an insult that reverberated throughout the Chinese American community for decades.

Half a century later, in 2019, Connie delivered the commencement address at the 150th Anniversary of the Golden Spike, honoring the legacy of the Chinese railroad workers. She reflected, “It was a moment 50 years in the making. I was there to finish what was started by Philip Choy.” (AsAm News, 2020).

It was a moment 50 years in the making. I was there to finish what was started by Philip Choy.

The spirit of Philip and Connie's work continues today through initiatives such as the Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project at Stanford University, which seeks to recover the stories of these unsung heroes.

Meeting Allies: Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars

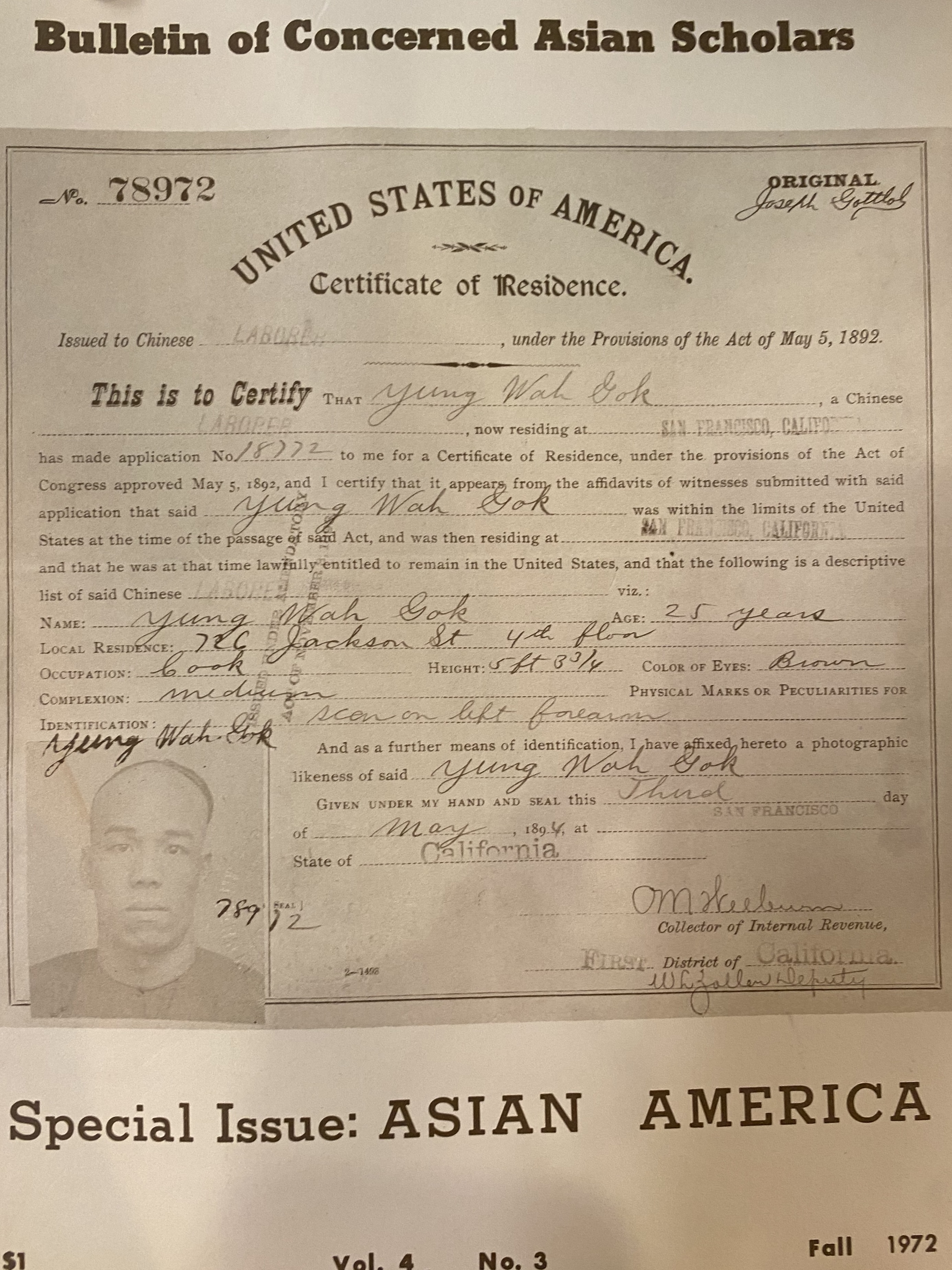

Left: Journal cover featuring the certificate of residence, or "chak chee," of Connie's grandfather Yung Wah Gok.

After Connie and her family moved to Los Altos in 1970, she became involved in the anti-war peace movement and encountered a group identifying as Asian Americans—a new and transformative concept for her. She was inspired by their political message of anti-racism and anti-imperialism to join in demonstrations and take up their chant of “One struggle, many fronts.”

In 1972, Connie contributed to the first Asian American issue of the Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars. Through her work, she began to draw connections between her family’s experiences and oppression of other people of color, such as the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. “That’s when I got into the whole sensibility and made connections,” she reflected.

The issue’s cover featured her grandfather’s certificate of residence, which he was required to carry due to the Geary Act of 1892. During that time, Chinese Americans were routinely stopped by immigration officers and required to present their certificate; failure to comply risked detainment or even deportation.

It is but a cherished myth...that the United States is a nation of laws before which all men are equal. What we have in reality is...a nation which has used the law as a tool for the persecution and genocidal treatment of minorities.

- Connie Young Yu, "The Chinese in American Courts," Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, Volume 4, Issue 3, 1972

A Revelation: The Writing on the Wall

Left: Connie's maternal grandmother, Mrs. Lee Yoke Suey, who was detained on Angel Island. Photo courtesy of The Californian, Nov 2010.

In 1970, Connie became a part of what she described as the most successful advocacy movement she had ever joined. That year, a park ranger discovered Chinese poetry etched into the walls of barracks on Angel Island, which were slated for demolition. The ranger contacted a Japanese American professor at San Francisco State University who helped spread the word.

The barracks had once been used to detain and deport Japanese Americans during World War II. Before that, it served as a detention center for Chinese immigrants following the 1882 Exclusion Act. Connie’s own grandmother had once been detained on Angel Island for 15 months due to the passage of the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act. Despite being the widow of an American-born citizen, who was returning home after the death of her husband, Connie’s grandmother was classified as an “alien ineligible for citizenship” and barred from entry. The building, along with the newly-discovered poetry, stood as a tangible reminder of the legacies of exclusion, detention, and deportation that had haunted the lives of countless people such as Connie's grandmother—and was now at risk of being erased.

A group of activists including Connie organized to form a committee to save the barracks from demolition. Their strategy was to “go through the system.” They contacted an assemblyman to draft a resolution that led to the creation of the Angel Island Immigration Station Citizens Advisory Committee. Through their efforts, Angel Island was designated a National Historic Landmark which ensured the preservation of the barracks. Today, the Angel Island Immigration Station still stands as a national monument where visitors can go and look at the “writing on the wall.”

Returning Home: The Story of San Jose's Chinatowns

Above: The fire that destroyed Market Street Chinatown in May 1887. White spectators gather in the foreground. Photo courtesy of History San Jose via New York Times (2021).

In the 1980s, the excavation for the construction of the new Fairmont Hotel in San Jose led to an unexpected discovery—an entire Chinatown that once stood on Market Street. For Connie, this discovery became “the heart of the story that I want to tell.”

This is the heart of the story I want to tell.

- Connie Young Yu, oral history, 2024

A century ago, Connie’s grandfather had lived and worked in this Chinatown as a young boy. However, the economic depression of the era fueled widespread hostility towards the Chinese. In 1887, tensions erupted into violence when arsonists set fire to the Market Street Chinatown.

As the fire spread, residents rushed to the water tower, only to find it had been mysteriously emptied. A crowd stood by and watched as Chinatown burned to the ground. Over 1,000 residents lost their homes, including Connie’s grandfather, who was forced to flee to San Francisco for refuge.

City officials openly celebrated the destruction On May 5, 1887, the San Jose Daily Herald declared, “Chinatown is dead. It is dead forever.”

But not everyone rejoiced. John Heinlen, a progressive German immigrant, announced plans to lease land to the displaced Chinese residents to rebuild a new Chinatown. His efforts sparked intense backlash—the city filed an injunction against him, and protestors staged a torchlight parade to denounce him.

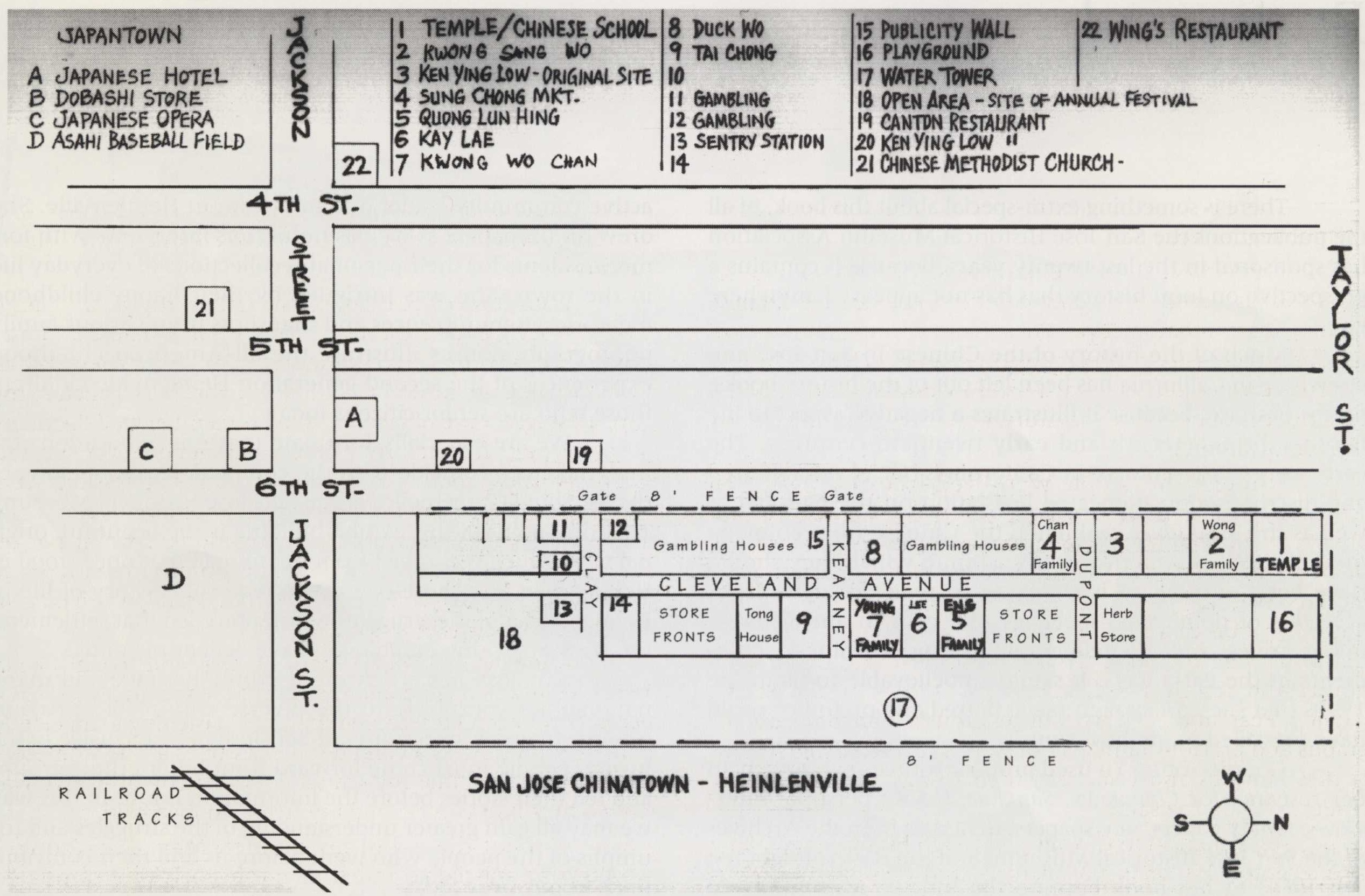

Despite opposition, Heinlen and the Chinese community persevered. The new Chinatown, named Heinlenville, was designed with brick buildings to withstand fire and a tall fence with barbed wire to keep out violence. It was built to be a safe haven that was here to stay.

Left: View of Heinlenville circa 1900, with the Ng Shing Gung temple on the far right. Photo courtesy of The Californian, Oct 2016.

This was where Connie’s grandfather later returned, and where her father was born in 1912. At its peak, Heinlenville was a thriving neighborhood home to around 300 residents. Connie’s father fondly recalled a childhood filled with festivals, games, and a tight-knit community. The Ng Shing Gung temple stood at the heart of Heinlenville and served as a religious, cultural, and social center.

However, the legacy of exclusion laws against Chinese immigrants eventually took their toll. As the younger generations moved out, no one moved in. By the 1920s, its population had dwindled.

In 1931, during the Great Depression, the Heinlen estate went bankrupt. Heinlenville was demolished to make way for the city's Corp Yard. The Ng Shing Gung temple, the last standing structure, remained until 1949 when the city declared it a fire hazard and tore it down. Only the temple altar was preserved.

By then, the few remaining Chinese residents, including Connie’s grandparents and father, had moved across the street to join San Jose’s growing Japantown and Pinoytown. “To me,” Connie said, “that became the first Asian American community in Santa Clara County.”

Dr. Tokio Ishikawa, who grew up in Japantown, said, “The Japanese came here because the Chinese were here…There was nowhere else to go. We came here and we were able to have a community and we were able to live together.”

For four decades, a vacant lot stood where there had once been a vibrant Chinatown. However, in 1987, the Chinese Historical and Cultural Project started an initiative to restore the altar and build a replica of the original temple. In 1991, the project was completed, and today it stands as the Chinese American Historical Museum of San Jose.

Left: The Ng Shing Gung temple replica today. Photo courtesy of The Californian, Oct 2016.

The archeological excavation that brought this history to light also led San Jose to confront its past. In 2021, Connie helped draft the resolution formally apologizing for the city’s role in the destruction of its Chinatowns, which was unanimously passed.

Reflecting on the impact of her remarkable efforts, Connie said, “The legacy…is this community…called Japantown…and how it has become this community for all peoples. But the roots are an Asian American community that came out of struggle, out of prejudice.”

Above: Map of Heinlenville drawn from memory by a former resident. Photo courtesy of "Chinatown, San Jose, USA."

The legacy...is this community...called Japantown...and how it has become this community for all peoples.

- Connie Young Yu, oral history, 2024

Where Next?

Learn More

- "Chinatown, San Jose, USA" by Connie Young Yu, published 1991 - book that tells the story of San Jose's Heinlenville Chinatown, from its beginnings in 1887 to its eventual decline and downfall in 1931.

- "Home Base: A Chinatown Called Heinlenville" by Jessica Yu, released 1991 - short film that features oral histories of former Heinlenville residents.

- "Special Issue: Asian America," Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars (now Critical Asian Studies), Volume 4, Issue 3, published 1972 - journal featuring essays, articles, and poems from contributors including Connie Young Yu, Shawn Wong, Frank Chin, Sam Tagatac, Lawson Inada, and Wing Tek Lum.

- "John Heinlen's Legacy: Chinatown & Japantown, San José," The Californian, Number 43, published October 2016 - quarterly magazine published by the California History Center featuring the history of Heinlenville.

- "Detained at Liberty’s Door: Exhibiting a Legacy," The Californian, Volume 31, Number 2, published November 2010 - quarterly magazine published by the California History Center featuring the story of Connie Young Yu's maternal grandmother who was detained on Angel Island.

- Resolution No. 80238, the resolution issued by the City of San Jose on September 8, 2021 that formally apologized for the city's role in the destruction of its historical Chinatowns.